Why derivatives play a bigger role in trading than you think

A derivative is a contract whose value comes from something else—like a stock, bond, index, currency, or commodity. Traders use derivatives to hedge risk, speculate on direction, and fine-tune exposure with far less capital than buying the asset outright.

Derivatives derive value from an underlying asset or index.

Futures, options, swaps, and forwards are the main types.

Uses include hedging, speculation, income, and arbitrage.

Key risks are leverage, liquidity, and counterparty exposure.

What are derivatives? (derivatives meaning)

In finance, a derivative is an agreement between parties whose price depends on an underlying reference—think of crude oil, S&P 500, EUR/USD, or even interest rates and volatility indexes. The contract itself is the product; you’re not buying the barrels of oil or the shares—you’re agreeing on how to settle the change in their value. This design lets investors transfer risk, express a view, or lock in a price without owning the underlying.

Why derivatives matter

Derivatives power much of the modern derivatives market because they solve real problems. An airline can lock fuel costs months ahead. A portfolio manager can insure stocks before earnings season. A global manufacturer can fix next quarter’s exchange rate. By separating price risk from ownership, derivatives make markets more flexible, more liquid, and—when used properly—more efficient.

Types of derivatives (derivatives and its types)

Although the product universe is huge, four families dominate everyday trading:

- Futures are exchange-traded contracts to buy or sell an asset at a set price on a set date. They’re standardized, centrally cleared, and marked-to-market daily. Equity index futures, Treasury futures, and WTI crude futures are staples for institutions and active traders.

- Options grant the right, not the obligation, to buy or sell the underlying at a preset strike before or at expiry. Calls benefit when prices rise; puts benefit when they fall. Options are versatile because they let you shape payoff: capped risk for buyers, income for sellers, and tailored spreads for complex views.

- Swaps exchange one stream of cash flows for another—most commonly fixed vs. floating interest payments. Corporates and banks use interest-rate swaps to reshape debt exposure without refinancing.

- Forwards resemble futures but are private, over-the-counter agreements with bespoke terms (size, date, credit). Many FX hedges are done via forwards because they can be tailored to a company’s exact cash-flow date.

How derivatives work under the hood

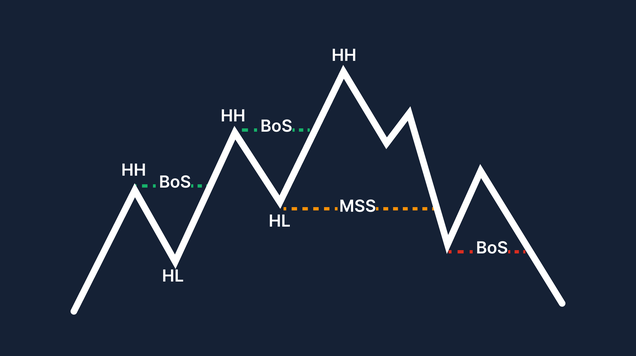

Every derivative links to an underlying through a pricing model grounded in “no-arbitrage” logic. For futures, the fair price reflects spot price plus carry costs (financing, storage, dividends). Options embed probabilities via implied volatility and are sensitive to the Greeks—delta (direction), gamma (curvature), theta (time decay), vega (volatility). In practice, most exchange-traded products settle daily by variation margin, which reduces build-ups of credit risk. Over-the-counter trades increasingly pass through clearinghouses for the same reason.

Derivatives in the stock market

When people ask about derivatives in stock market contexts, they usually mean index futures and listed equity options. Index futures let managers quickly raise or reduce equity exposure without touching hundreds of individual names. Options enable protective puts, covered-call income, or structured payoffs around catalysts. Single-stock options add precision—hedging a specific name, building income on long holdings, or expressing a soft-bullish view via call spreads.

What derivatives are used for (derivatives examples)

Hedging: A wheat farmer sells futures to lock a harvest price; a fund buys puts on an index to cap downside during uncertainty.

Speculation: A trader buys oil call options before OPEC decisions, risking the premium for asymmetric upside.

Income: An investor sells covered calls on a stock position to harvest option premium while willing to sell the shares at a higher strike.

Arbitrage & basis trades: Professionals exploit small gaps between spot and futures, or between options and their theoretical value, helping keep prices aligned.

The role of leverage—friend and foe

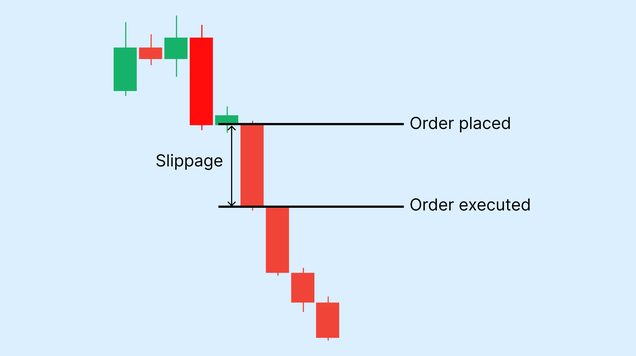

Derivative trading is capital-efficient because margin requirements are a fraction of the full notional exposure. That’s a feature, not a flaw, but it cuts both ways. A 1% move in the underlying can swing profit and loss dramatically when your contract controls 10x–50x your cash. The answer isn’t fear; it’s position sizing. Define risk first, then work backward to contract count, strike, and expiry.

Choosing the right tool for the job

If your goal is to lock a future price, futures or forwards are direct and linear. If you want insurance with limited cost, options fit because your maximum loss is the premium. For income on existing holdings, covered calls or cash-secured puts keep risk transparent. To fine-tune rates exposure, plain-vanilla interest-rate swaps are standard corporate tools. The instrument should mirror the risk you actually care about; don’t use a complex exotic when a simple future or put will do.

Practical scenario walk-throughs

- Equity hedge: A diversified stock portfolio is up 18% YTD, but policy risk looms. Buying a three-month at-the-money index put caps potential drawdown without selling core positions. If markets stay calm, the “insurance” cost is limited to the option premium.

- Currency certainty: A European exporter invoices in dollars, gets paid in 90 days, and worries the USD might weaken vs. EUR. A forward contract locks today’s EUR/USD rate, stabilising the upcoming cash flow.

- Commodity budgeting: A regional airline books jet-fuel swaps at fixed prices for the next two quarters. If spot fuel spikes, the swap’s gain offsets the higher purchase cost; if fuel falls, the swap loses but the airline buys cheaper fuel—either way, budgets become predictable.

Getting started in derivatives trading—without the traps

Begin with education and a paper account. Learn how margin, expiries, and settlement work. On options, master how theta and implied volatility shape returns: buying calls into a volatility crush can lose money even if the stock rises modestly. Start with small size, clear exit rules, and products with healthy liquidity. Keep notes—what thesis you had, why the specific contract, how the Greeks evolved—and review outcomes monthly. The most durable edge in derivatives trading is discipline.

Derivatives are the toolkit of modern markets. They transfer risk to those willing to hold it, unlock precision that spot markets can’t offer, and—used thoughtfully—can protect portfolios or amplify well-researched ideas. Understand the types of derivatives, match the tool to your objective, respect leverage, and let position sizing do the heavy lifting. That’s how financial derivatives become an asset, not a hazard.

FAQs

What are derivatives, in one sentence?

Contracts whose value depends on an underlying asset, index, rate, or event.

Which are the main types of derivatives?

Futures, options, swaps, and forwards—plus many variations built on these cores.

Are derivatives only for professionals?

No. Listed options and futures are accessible to individuals, but education and risk limits are essential.

Can derivatives reduce risk rather than increase it?

Yes. Hedging with puts, futures, or forwards can stabilize portfolios and cash flows when used with a clear plan.