Fed using rising term premiums to keep interest rates on hold

The Fed is using an increase in the term premium as a reason for keeping interest rates on hold. It is a potentially dangerous strategy.

Yields on longer dated bonds will typically – under normal market conditions – be higher than those found on shorter dated instruments. This excess return represents the added protection investors require to persuade them to hold longer term instruments as opposed to simply buying and repeatedly rolling over shorter dated bonds. In a sense it is the insurance premium investors demand to protect themselves against unforeseen risks and market developments that they will be more heavily exposed to when locked into a longer-term investment. It is commonly referred to as the ‘term premium’.

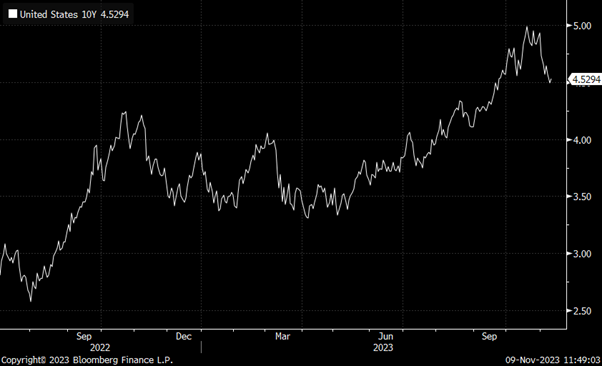

The chart below shows how yields on 10-yr Treasury bonds have risen sharply over the past six months or so. This move cannot be explained solely by the increases seen in the US Federal Reserve (Fed) Funds rate but is the result also of an increase in the term premium, a development which has been cited by the Fed as a key reason for why it currently sees no need for further interest rate rises: this additional tightening being provided by the term premium is essentially doing the work of the Fed for it, dampening down economic activity, squeezing growth and, by implication, applying downwards pressure on inflationary pressures.

Reasons for explaining why the term premium has risen are numerous. Typically it will rise when an economy is facing a potential downturn, leaving investors uncertain or in disagreement about future bond yields, this uncertainty leading to a higher premium being demanded to compensate for the risk of investing long term amid such uncertainty. These are conditions which are currently being seen in the US. It may also represent the impact of a central bank’s forward guidance, or an upwards revision to the market estimates of the neutral interest rate. But the key point is that what drives the term premium is impossible to accurately pin-point. It may be one factor or, more likely, a combination of several factors. And this is the problem for the Fed. Nobody knows exactly how to calculate the term premium, and, by implication, what specific factors drive it higher or lower. There are a whole host of reasons why the term premium may rise or fall, but it is virtually impossible to confidently suggest what factor is dominant at any particular time. And this is the concern with the Fed using the increase in term premiums as a justification for keeping interest rates on hold: if it cannot fully understand why the term premium has risen, then it follows it has no clear understanding either of when or why it might fall again. It is an unknown variable.

This problem with the term premium can be seen elsewhere, such as in the recent funding plans released by the US Treasury. This showed that planned issuance in the longer end of the curve is being reduced in favour of skewing issuance towards instruments with shorter maturities that have less of a term premium attached to their yield. This clearly shows the term premium is not just a monetary phenomenon but rather reflects economy-wide risks, encapsulating everything other than just the expected path of short-term interest rates.

Intuitively, the Fed’s decision to pause its monetary tightening makes sense. If market rates are already high, then raising official interest rates further risks an over-tightening. Or, at the other extreme, may have little impact at all on longer term rates, instead simply closing the gap between the official and market rates. But to do so based on movements in the term premium is dangerous. If the term premium has risen because of the Fed’s forward guidance, then clearly Powell and his colleagues will need to be mindful of the language they use going forward. Similarly, if it is because expectations of the neutral Fed Funds rate have risen, then the Fed will need to be alert to these expectations being revised lower again, which could prompt the term premium to fall just as quickly as it has risen. To be basing monetary policy on such an unknown variable is clearly something of a gamble, potentially leaving the US economy at risk of an inappropriate monetary stance.

While there is nothing inherently wrong with shifting monetary policy away from a tightening trajectory and onto a ‘higher for longer’ footing when financial conditions are tight, prudence suggests that such a shift should be predicated on a more solid understanding of why yields are higher rather than on a simple assertion that the term premium has risen. To do so suggests the Fed does not really know itself precisely why financial conditions have tightened as they have. The result is that the Fed is leaving monetary policy exposed to the vagaries of the market and open to the risk that further hikes – or cuts - in short-term rates may yet be needed if the same degree of financial restraint is to be kept in place.