Is the Fed risking over-tightening monetary policy?

Requirement for labour market easing means loss of jobs and output

2022 was very much unprecedented in terms of the monetary tightening delivered by the US Federal Reserve (Fed) in recent times. Yet despite the tightening delivered so far, inflationary pressures remain strong with CPI remaining significantly above target, albeit data suggesting that peak inflation has now passed.

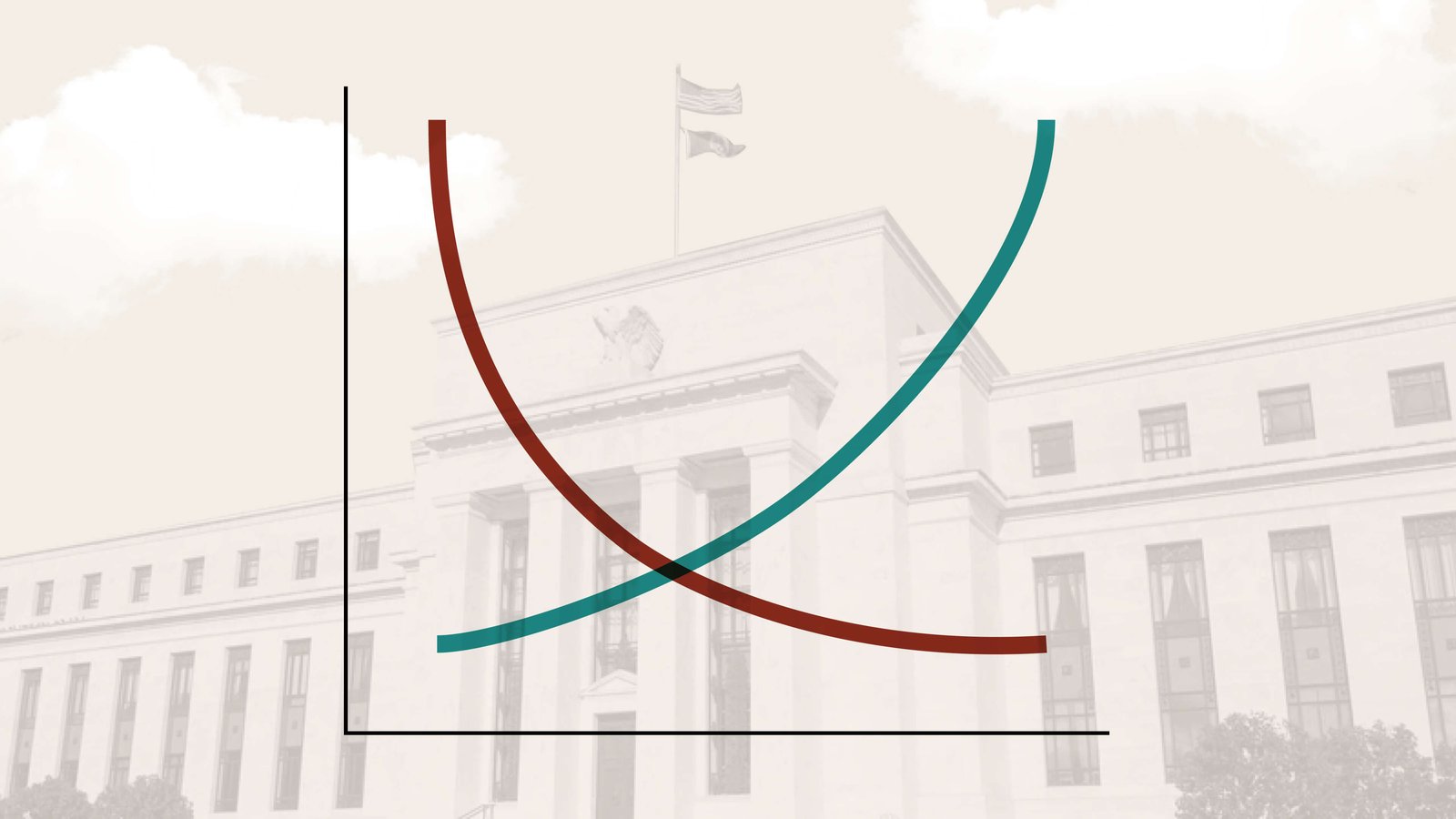

One reason offered for this on-going strength has been the labour market, the Fed warning that tight labour market conditions are pushing up wages which are in turn fuelling inflation. This has led Fed officials to frequently warn that monetary policy will remain on a tightening trajectory until the labour market begins to loosen, with policymakers all the way up to Powell warning that the market may be underestimating the eventual terminal rate of interest. Clearly the Fed sees a trade-off between a tight labour market and elevated levels of inflation, ie the classic Phillips curve.

What is the Phillips curve?

The Phillips curve is an economic theory that says inflation and unemployment have a stable and inverse relationship. This means that episodes of high inflation can be expected to be associated with low levels of unemployment (and by consequence higher wages growth), and vice versa. The implication for the Fed is that if inflation is above target and needs to be brought lower, then this can be done, but at the expense of a higher level of unemployment. The solution to higher inflation, therefore, is to tighten monetary policy sufficiently to cause a slowdown in economic activity, prompting firms to shed labour and in turn facilitate a fall in labour renumeration and, by implication, a reduction in aggregate demand. As aggregate demand falls so too will the rate of inflation.

Much research has been conducted on the Phillips curve since it was first published in the 1950s. This has largely concluded that, while a short run trade-off between unemployment and inflation can be seen, it is not something that is observed in the long run. Moreover, the strength of this short run relationship appears to be weakening. For policy makers, this means that targeting a looser labour market as a necessary requirement for bringing down inflation is sub-optimal.

Nevertheless, judging from the Fed’s comments and actions to date, it seems the Phillips curve remains very much the primary framework it is using as it battles to bring inflation down.

Supply-side policies are required

Nobody would argue that shifts in aggregate demand driven by monetary policy changes have no impact on inflation and unemployment. They do, at least in the short run. But an analysis of the current drivers of CPI suggests the current strategy is wrong.

Inflation over the past three years has arguably stemmed from two main sources: the covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The covid pandemic created, amongst other things, severe disruptions in supply chains, creating shortages that allowed end-sellers to raise prices. But it also exerted upwards pressure on wages as firms sought to maintain or secure additional labour as absenteeism levels rose, through a combination of sickness and/or fear of leaving the home. The Ukraine war triggered sharp rises in global food and energy prices, the impact of which seeped into almost all corners of the economy. The Fed has no policy levers to directly control either of these pricing pressures, meaning its attempts to control CPI via demand-side management tools are sub-optimal. Clearly it is a supply-side response that is needed.

Unfortunately, the fiscal response from the US federal authorities simply served to magnify the inflationary problems being seen, with support measures such as the Pay-check Protection Program and Consolidated Appropriations Act boosting aggregate demand at the same time as supply was contracting. Rather, what was required were measures to boost the labour participation rate, probably the largest structural impediment now facing the US labour market and playing a key role in driving wages higher.

The US participation rate remains around 1% below its pre-covid level and some 5% below the peak levels seen around the turn of the century. The numbers of long-term unemployed remains high while there appears to have been a permanent increase in workers opting to drop out of the labour market altogether. These may be a consequence of long-term health issues associated with covid infections or simply a re-appraisal of work/life balances. But whatever the cause, this labour shortage is showing up in higher wages, in turn boosting inflationary pressures as firms seek to recoup these higher costs. Simply boosting demand has done nothing to persuade these workers to return to work. Where the federal government should have been implementing policies to raise the participation rate, boosting aggregate supply and in turn lowering wages, the Fed has been left to achieve this goal via a policy of demand destruction.

Where does this leave the Fed?

Evidence is pointing to inflationary pressures having peaked. Global food and oil prices have fallen back to levels seen prior to the start of the Ukraine war and supply chains are improving, and look set to improve further as manufacturing output in China accelerates following the end of the zero-covid policy. And average hourly earnings are reverting to pre-covid levels. These factors have all contributed to headline annual CPI having now fallen each month since last June, albeit remaining at elevated levels.

This now leaves the Fed in the position of simply needing to dampen down inflation expectations to prevent them from feeding into wages growth and triggering second and third round effects, as was seen in the 1970s. And it is arguable that the Fed has indeed succeeded in doing this. The feared wages/price spiral has not materialised - as the Fed itself has acknowledged - while inflation expectations are similarly showing no signs of running away. The 5yr/10yr inflation expectation has remained unchanged at 2.9% for 3 months and has been stuck in a narrow 2.7%-3.1% range since January 2021. The Fed has done its job - no further tightening in monetary policy is needed.

But the allure of the Phillips curve is hard to break…

But the Fed still believes the labour market is too strong and wages growth needs to be brought down, and further interest rate rises therefore look certain to be delivered. It is expected to raise rates by 25bps at both its March and May policy meetings and is currently assigned an approximate 50/50 chance of hiking by a further 25bps in June, these further hikes almost solely predicted on the need to ‘loosen’ the labour market, central bank speak for saying that ‘jobs need to be lost’.

Clearly the allure of the Phillips curve and the simple policy decisions it offers remains too much for the Fed to ignore. But the consequence of this addiction is an unnecessary destruction of output, an excessive number of lost jobs and a potential screeching reversal in monetary policy in the not-too distant future.

..a looser labour market is central bank speak for jobs must be lost...