United Kingdom Between inflation and stagnation

The UK economy is currently caught in a classic squeeze. On one side, the labor market is finally showing the cracks that high interest rates were designed to create. On the other, inflation remains a stubborn guest that refuses to leave quietly, leaving the Bank of England with very little room to maneuver.

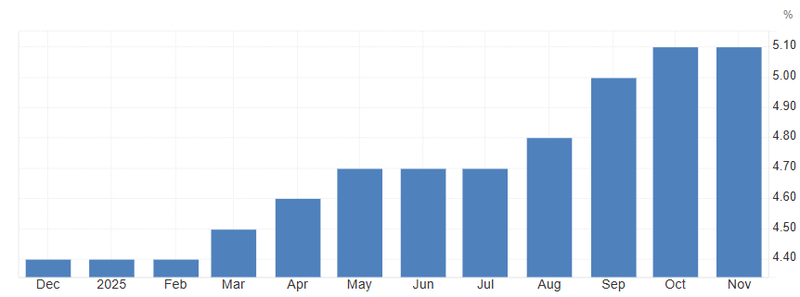

First time since 2021, the unemployment rate has hit 5.1%.

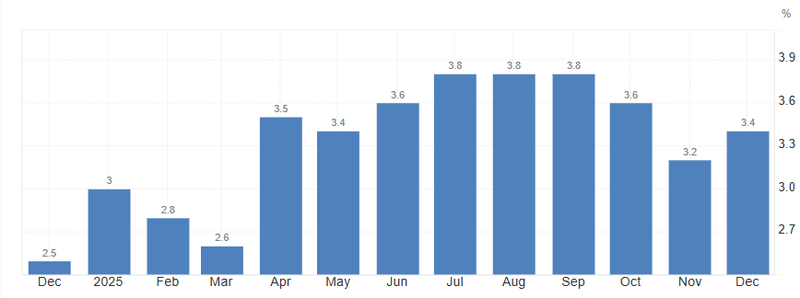

Inflation sitting at 3.4% is a bit of a double-edged sword.

Keep rates high to ensure the 3.4% inflation doesn't bounce back.

Labour market 5.1%

Unemployment at 5.1% may not sound dramatic, but it’s a clear shift. For the first time since 2021, the labour market is no longer tight and it’s loosening.

The balance of power has changed. The post-pandemic period, when workers could command higher wages and switch jobs with ease, is fading. Employers aren’t just pausing recruitment anymore; they’re actively managing headcount. The urgency to hire has been replaced by the need to protect margins.

Higher interest rates are weighing on businesses, and the rise in employer National Insurance contributions has added another layer of cost. When companies look to defend profitability, staffing is often the quickest adjustment. This isn’t disorder, it’s deliberate scaling back.

If the unemployment rate continues to creep higher in the months ahead, the narrative will shift decisively. What is currently described as a “cooling” labour market could start to look like something more fragile. And once that perception takes hold, pressure on the Bank of England will intensify.

Source: Office for National Statistics

Inflation stuck above comfort

At 3.4%, the crisis phase is over. The comfort phase hasn’t begun.

The issue now isn’t energy spikes or supply shocks. It’s services. That’s where inflation is proving stubborn, and that’s what keeps the Bank of England uneasy. Sticky service prices suggest wage pressures are still embedded in the system. Even with unemployment edging higher, policymakers worry that underlying inflation hasn’t fully cooled.

For households, this doesn’t feel like progress. Prices aren’t surging anymore, but they’re still climbing faster than the Bank’s 2% target. Pay packets are stabilizing, yet genuine purchasing power isn’t meaningfully improving.

What the Bank needs is clear evidence that inflation is decisively heading back to target not drifting, not pausing, but genuinely converging. For now, that reassurance simply isn’t there.

Source: Office for National Statistics

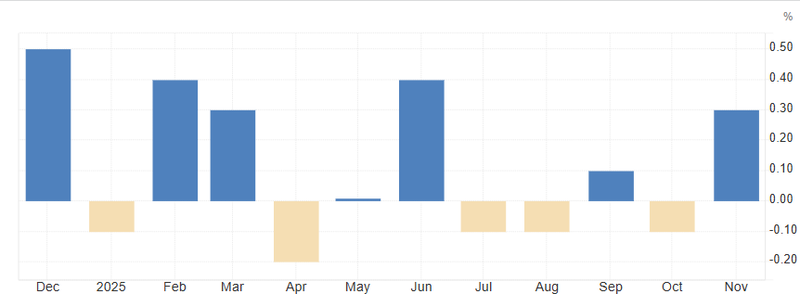

Growth, stagnation in slow motion

After a modest 0.3% expansion previously, a slowdown to 0.1% would send a clearer message than the headline suggests. Yes, it’s still technically growth but it’s a sharp loss of momentum. An economy that was barely moving is now barely crawling.

The UK remains stuck in first gear. Frozen tax thresholds continue to squeeze households quietly but persistently, trimming disposable income without the drama of a tax hike. Consumers are cautious by instinct now, not just necessity. Businesses aren’t scrapping projects outright, but they are delaying decisions, stretching timelines, and waiting for clarity on borrowing costs before committing capital.

The shift from 0.3% to 0.1% may look small on paper, but direction matters more than level. Momentum is fading, not building.

Stagnation doesn’t shock it lingers. It drains confidence gradually, dulls risk appetite, and reshapes expectations about the future. And the longer growth hovers near zero, the more difficult it becomes for policymakers to argue that restrictive policy is still appropriate.

Source: Office for National Statistics

The Bank of England, April is the real window

A 5–4 vote to hold rates at 3.75% is not a comfortable pause it’s a divided committee buying time. This isn’t a debate about whether rates will eventually fall. It’s a debate about timing and credibility. Cut too early, and inflation risks flaring back up. Wait too long, and the slowdown hardens into something more painful.

Right now, the Bank doesn’t have enough evidence to move. Inflation is easing, but not convincingly. Growth is weak but not collapsing. The labour market is softening but not yet deteriorating sharply. That combination keeps policymakers frozen.

April changes the equation

Bank will have several more months of labour data and a clearer inflation trend. If unemployment continues edging higher and GDP flatlines, the argument for holding steady becomes harder to defend. More importantly, a move in April would look deliberate, not panicked. It would signal control.

The base case is straightforward, no immediate cut. Rates stay where they are while the data accumulates. But if the current drift continues soft jobs, near-zero growth, gradually cooling prices.

Not the start of an aggressive easing campaign. Not a rescue mission. Just the first acknowledgment that policy has been tight enough. And when the Bank finally moves, it will want the data and the narrative firmly on its side.