What is an Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF)? General overview

An exchange-traded fund (ETF) is a regulated investment fund that trades on stock exchanges at market prices, much like a stock. Unlike a single-company share, an ETF aggregates a basket of assets—equities, bonds, commodities, and more—delivering diversification through one ticker at generally competitive costs. A creation/redemption mechanism helps keep the ETF’s market price close to its net asset value (NAV), although small premiums or discounts can arise, particularly in volatile markets.

An ETF is a regulated fund listed on global stock exchanges, which concentrates a basket of assets under the same ticker symbol.

The creation/redemption process helps align the ETF's price with its NAV (net asset value). ETFs can be traded at a premium or discount to the NAV, especially in volatile markets.

There are a variety of risks when trading ETFs, including market risk, liquidity risk, and counterparty risk.

ETF CFDs allow traders to speculate on the price of the fund, increasing the profit potential due to the leverage factor, although it also increases the risk of loss.

Definition and relevant aspects

An ETF is an exchange-listed product that pools investor capital to purchase a portfolio of securities with the objective of replicating the performance of an index, a commodity, or a business sector. Operationally, the fund collects contributions from investors and is managed by a registered and regulated adviser. While the primary use case is long-term investment, ETFs are also widely employed for hedging and tactical speculation.

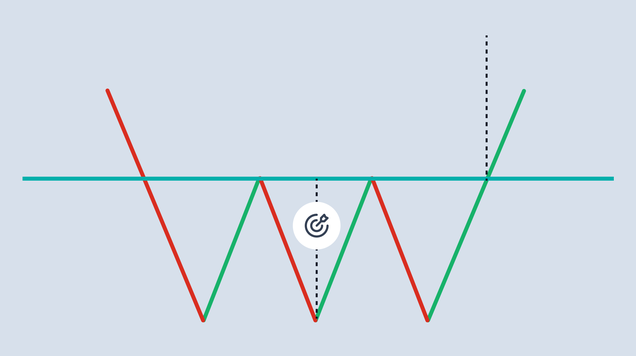

How does the price of the ETF stay close to the value of the asset it seeks to replicate? (creation and redemption mechanics)

The creation and redemption process helps keep an ETF’s market price close to its NAV. Authorized participants (APs)—typically institutional investors and market makers—transact with the fund sponsor: they create ETF shares by delivering the prescribed basket of underlying securities and redeem shares by returning ETF units in exchange for that basket. Through disciplined buying and selling in the secondary market, APs generally limit deviations; when gaps appear, they seek to close them. Beyond aligning price and NAV, this process supports ETF efficiency and liquidity (ETF.com 2025).

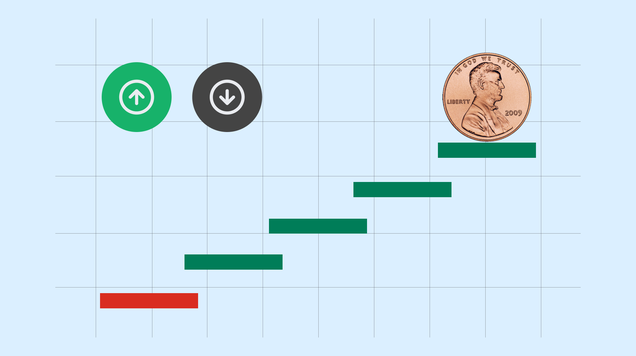

Price and NAV; premium and discount implications

ETFs have two principal value references:

- NAV (Net Asset Value): typically calculated at the close of the market (some funds also publish an indicative value intraday).

- Market price: a continuously traded price determined by supply and demand.

When the market price trades above NAV, the ETF is at a premium; below NAV, it trades at a discount. In periods of relative stability, market price and NAV tend to be close. During heightened volatility or when underlying markets are less liquid, the gap can widen. The creation/redemption mechanism helps reduce such divergences over time (Fidelity 2025).

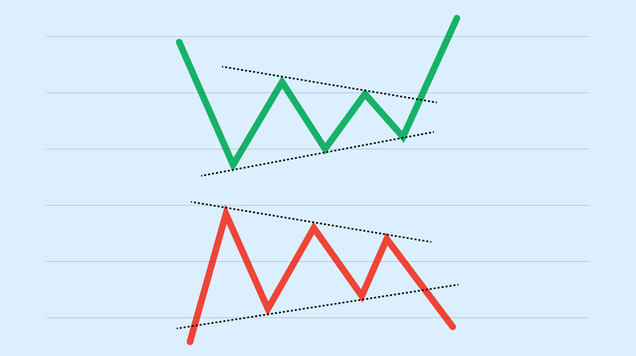

Physical and sample replication vs. synthetic replication

Index-tracking ETFs may:

- Replicate physically, purchasing all constituents or, via sampling, a representative subset when the index is very large.

- Replicate synthetically, using derivatives such as swaps to mirror index performance without holding all underlying assets. Synthetic structures introduce counterparty risk that does not arise in the same way with physical replication. The replication approach is disclosed in the ETF’s prospectus.

Liquidity implications when trading ETFs

An ETF’s tradable liquidity depends not only on its own on-screen volume but also on the liquidity of its underlying holdings. Broad, liquid exposures (e.g., large-cap equities or major bond benchmarks) typically exhibit tighter bid–ask spreads and smaller premiums/discounts. In thinner markets, spreads tend to widen, increasing the likelihood of noticeable premium/discount effects (ETF.com 2025).

Risks involved in trading ETFs

- Market risk: Exposure to underlying price fluctuations can produce losses if markets move against the position.

- Liquidity risk: In less-liquid markets, wider spreads, execution slippage, and larger premium/discount gaps are more likely.

- Counterparty risk: Present in synthetic ETFs due to the use of derivatives; the prospectus should be reviewed to understand the structure and associated risks.

Types of ETFs

- By asset type: equities, fixed income, commodities, stock indices, sector indices.

- By style or strategy: factor investing (value, momentum, quality), dividend strategies, ESG, sector diversification, among others.

- By management: indexed (passive) or actively managed ETFs.

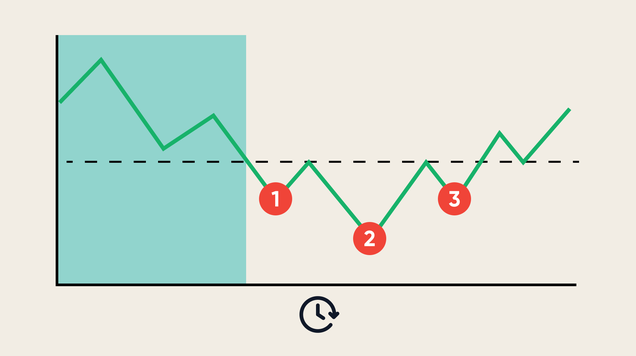

What are ETF CFDs and how do they work?

An ETF CFD allows a trader to speculate on the ETF’s price movements without owning the fund’s holdings. Positions can be long or short and may employ leverage, which raises profit potential but also amplifies loss risk. The ETF’s inherent diversification still informs the exposure, yet CFDs are derivative instruments, so trading becomes more precise and more complex. All inherent risks should be understood before using CFDs.

Trading costs on ETF CFDs

In contrast to paying a transaction fee and an ETF’s management fee when buying fund shares directly, CFD trading entails trading and financing costs. The most common are the spread (difference between buy and sell) and the overnight commission (swap) for positions held beyond the trading day. Because the spread is incurred each time a CFD position is opened or closed, more dynamic trading typically results in higher aggregate costs. Dividend adjustments may also apply if the ETF’s constituents go ex-dividend.

Operations in practice

ETF CFDs generally reflect the trading hours, liquidity behavior, and price dynamics of the underlying market. Because CFDs trade over the counter, there may be broker-specific differences in execution windows, margining, or how corporate actions are handled. Understanding these operational and risk implications is essential for confident, responsible trade management.

Conclusion

ETFs offer diversification, access to professional portfolio construction, and an architecture capable of expressing advanced strategies through a single ticker. ETF CFDs extend those exposures to short-term trading with leverage—enhancing return potential while increasing risk. Regardless of instrument, disciplined, informed management—grounded in product knowledge, cost awareness, and robust risk controls—is fundamental to achieving consistent outcomes.