What is the definition of arbitrage?

Arbitrage is the practice of buying an asset where it’s cheaper and selling it where it’s pricier—often at the same time—to lock in a near-riskless profit.

Arbitrage meaning: profit from price differences for the same (or equivalent) asset.

Arbitrage trading: buy low, sell high—simultaneously—across markets or instruments.

Opportunities are rare, short-lived, and highly competitive.

Costs, speed, and execution risk determine whether a trade is truly “risk-free.”

Definition of arbitrage

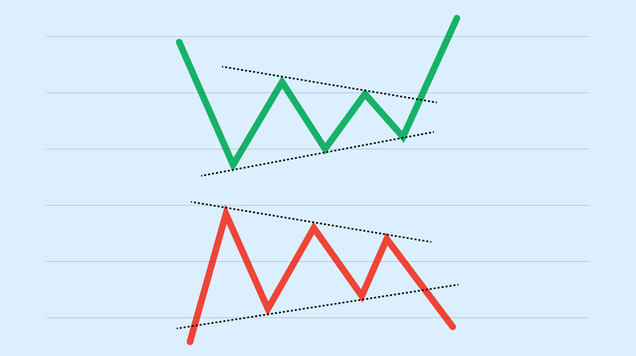

When people ask “what is arbitrage?”, they’re asking about one of finance’s oldest ideas: the law of one price. In an efficient market, identical goods should trade at the same price. When they don’t—because of latency, segmentation, or supply/demand quirks—arbitrage steps in. A trader buys in the cheap venue and sells in the rich venue, ideally at once, capturing the spread. That’s arbitrage trading in a sentence.

In the textbook version, arbitrage is riskless. In the real world, it’s low risk—not no risk—because you face execution delays, funding constraints, and market micro-structure hiccups.

Why price gaps appear

Even in liquid markets, tiny mismatches occur. Different venues update at different speeds. Some investors face settlement or borrowing frictions. Taxes, fees, and regulation vary by region. Corporate actions (mergers, conversions, index rebalancing) temporarily distort prices. Arbitrageurs compete to close those gaps; their trades, in turn, make markets more efficient by pulling prices back into line.

Common types of arbitrage

- Geographic (spatial) arbitrage. The same stock or ETF trades on two exchanges at slightly different prices. Buy in the cheaper market; immediately sell in the pricier market.

- Triangular FX arbitrage. Currency A/B, B/C, and A/C should multiply consistently. If they don’t, trade all three pairs to net a tiny, near-instant profit.

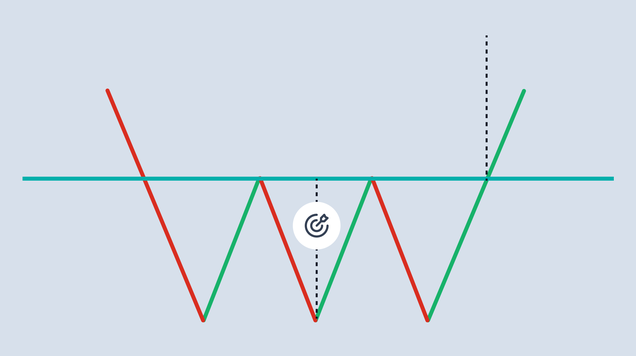

- Cash-and-carry (temporal) arbitrage. When a futures contract trades above fair value, buy the underlying (spot), short the future, and hold until convergence at expiry. The reverse—reverse cash-and-carry—applies when futures are too cheap.

- Merger (risk) arbitrage. When Company X agrees to buy Company Y for a fixed consideration, Y trades at a discount to the deal value. Arbitrageurs buy Y (and sometimes short X) to earn the spread if the deal closes. This is not riskless—deals can fail.

- Convertible or index arbitrage. Long a convertible bond and short the issuer’s equity to isolate mis-priced optionality; or trade index futures vs. baskets of stocks when the derivative deviates from fair value.

- Cross-asset/derivative parity. No-arbitrage relationships like put-call parity or covered-interest parity in FX anchor pricing; when they drift, arbitrage restores balance.

- Crypto and exchange-to-exchange arb. Fragmented venues, different stablecoin pegs, and varying withdrawal fees create frequent but short-lived gaps.

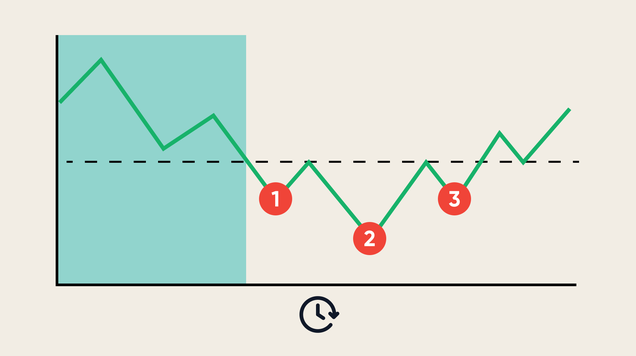

How an arbitrage trade actually works

Arbitrage is logistics plus math. You need simultaneous execution (or a locked hedge), borrow/shorting capacity for the leg you sell, clearing and settlement access, and funding that covers margin and fees. The workflow is simple to describe but hard to do well:

- Detect the mispricing (models, scanners, or pre-defined parity rules).

- Lock both sides—buy and sell—so market risk is neutralized.

- Finance the position (repo, margin, stablecoins, or internal capital).

- Carry and unwind until the instruments converge or the spread is captured.

If any link fails—your borrow disappears, fees jump, latency spikes—the “riskless” trade gains risk fast.

Costs, frictions, and “limits to arbitrage”

Three things turn pretty theory into tough practice:

- Transaction costs and funding. Spreads, commissions, financing (margin, borrow, swap), and withdrawal fees in crypto can erase the edge.

- Execution and latency. In competitive markets, mispricings last milliseconds; firms invest in co-location, microwave links, and smart routers to win the race.

- Model and basis risk. “Equivalent” isn’t “identical.” A future vs. a basket, a convertible vs. stock, or two share classes can diverge longer than your capital can wait.

Behavioral forces also matter. Crowded trades unwind violently when capital flees; regulation can cap leverage or shorten the list of eligible counterparties. These limits to arbitrage explain why small gaps persist.

Simple, concrete examples

1) FX triangular arbitrage (conceptual math).

Suppose EUR/USD = 1.1000, USD/JPY = 150.00, and EUR/JPY = 165.00. Multiplying 1.1000 × 150.00 implies EUR/JPY “should” be 165.00. If the actual quote were 165.40, there’s a 40-pip premium. You could sell EUR/JPY and simultaneously buy EUR/USD and USD/JPY in the right amounts to net the difference—after costs—until quotes line up.

2) Cash-and-carry with futures.

Spot oil is $80. The three-month future is $83, while carrying costs (financing + storage, simplified) imply fair value of $81.50. An arbitrageur buys spot oil, shorts the future, finances the inventory, and locks in the spread to expiry—provided costs and logistics are truly covered.

3) Merger arbitrage.

Acquirer offers $50 cash for Target, whose stock trades at $48.80. The $1.20 spread reflects deal risk and time value. If the deal closes in two months, annualized return might look attractive; if regulators block it, the stock can drop sharply. It’s arbitrage trading, but not riskless.

Is arbitrage legal?

Yes, provided you use public information and follow market rules. Classic arbitrage enforces fairness. What’s illegal is trading on material non-public information (insider trading), front-running client orders, or manipulating markets. Regulators encourage true arbitrage because it improves pricing and liquidity.

Can individuals do arbitrage?

Retail traders can capture micro-arbitrage—ETF premium/discount anomalies, minor crypto exchange spreads, funding-rate imbalances—especially on slower venues. But the easiest, purest gaps in major equities, futures, and FX are largely harvested by professional firms with speed, scale, and cheap financing. For most individuals, the smarter play is to learn no-arbitrage logic (so you don’t overpay) and use light forms of arb, like cash-and-carry in crypto or pairs trades with strict risk controls.

Why arbitrage matters to everyone

Even if you never place an arb trade, your prices are better because someone else does. Index NAVs track futures more closely; ETF prices hug underlying baskets; option quotes respect put-call parity. No-arbitrage is the backbone of derivative valuation models and the reason markets don’t spin into easy-money chaos.

Arbitrage—in its pure form—is buying low and selling high at the same time to capture a price discrepancy. Real-world arbitrage trading is a craft: tiny edges, fast execution, careful financing, and relentless attention to costs and risk. Understand the arbitrage meaning, recognize where gaps come from, and you’ll not only see why opportunities are rare—you’ll also see why markets, on most days, are astonishingly fair.

FAQs

Is arbitrage truly risk-free?

In textbooks, yes. In practice, you face execution, funding, and slippage risks. The goal is to minimize—not eliminate—risk.

How is arbitrage different from speculation?

Arbitrage targets a known price gap between equivalent assets; speculation bets on future direction without a locked hedge.

Does arbitrage exist in crypto?

Yes—fragmented exchanges, varying fees, and stablecoin frictions create frequent, short-lived spreads. Transfers and withdrawal limits are the main bottlenecks.

What skills or tools do I need?

Clean data, speed, access to borrow/shorts, low fees, and iron discipline. Without those, gaps that look juicy on paper won’t survive real-world costs.